SMALL CROWD HEARS ABOUT ARTIFICIAL TURF, FIELDS OPTIONS

Crowd supports move toward artificial, synthetic field to replace current football field

Athletic Director Jamie Rockhill opened the Fields Forum (June 15, 2017) with a short discussion outlining the process that led to the field study presented to the Board of Education in January and to the Athletic Field Master Plan that prioritizes the options involving the fields.

Athletic Director Jamie Rockhill opened the Fields Forum (June 15, 2017) with a short discussion outlining the process that led to the field study presented to the Board of Education in January and to the Athletic Field Master Plan that prioritizes the options involving the fields.

About 10 community members were at the forum at the Middle School cafeteria. They asked a variety of questions about the turf, ranging from injury rates and maintenance to striping the field and infill depth.

Superintendent Susan Swartz also said that the Board of Education at its meeting on Monday “agreed to look at the fields and what we need to do to fix them.” That could mean considering an artificial turf field and/or revamping all of the current natural turf fields on campus and at the schools.

She said any capital project involving the fields must also involved building work in order to get the maximum amount of state aid reimbursement. She said a prospective project would involved upgrading the high school auditorium and roofs on the seven buildings. That way, the project would be eligible for about 70 percent reimbursement from the state over 15 years.

Any capital project would be presented to the community as early as May 2018.

The fields at Scotia-Glenville are used by after-school athletic teams as well as by physical education students during the school day.

- Here is the Athletic Fields Master Plan presentation to the Board of Education on January 30.

- Here is the Athletic Field Master Plan that prioritizes the field work from March 10

- Here is the full Athletic Fields Master Plan (62 pages)

Mark Celenza from Chenango Contracting discussed artificial turf fields. He said his firm has been involved in many of the fields in the Capital Region, including at Amsterdam HS (among the oldest), Union College, Siena College, the University at Albany and the new turf field at Albany High School. The company has had more than 200 clients across New York.

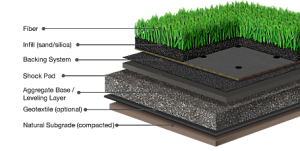

He said the firm determines how the field would most likely be used before recommending one of three types of fiber and the depth of the in-fill. “Remember, kids play on the infill, not the fibers. The thicker the infill is, the fewer injuries you tend to have,” said Celenza. He said that, compared with natural turf, artificial turf injuries tend to be less, especially with higher amounts of infill.

His company offers two types of turf: standard and elite. The standard line has a pad on the bottom with sand and rubber infill on top of that. The elite version of field has more infill (1.75 inches) and uses a cryogenic rubber that has gone through additional filtering processes. He said that 60% to 70% of area fields are the elite type. He said the elite tends to reduce injuries but also costs 10-15 percent more. By comparison, he said a regular turf field may cost in the $400,000 range with another $450,000 for the site preparation before the turf is put down. The elite version would add about $45,000 to $70,000 to the overall cost.

The fibers come in two main types: Monofilament and Slit-Film. The Slit-Film type is good for physical education classes and lighter uses of the field and tends to have a longer lifespan; monofilament is better for ball rolling sports like soccer and features individual blades of grass. It is not as durable at the Slit-Film. A third option involves a 50-50 combination of the two types of fibers that tends to work well for more uses and has almost the same durability and lifespan as Slit-Film.

As for maintenance, which involves running a rake through the infill to compact it, the cost is around $5,000 to $10,000 every four to six weeks. He said the company would train S-G maintenance workers to do that work in order to keep the field in the best shape. Annual maintenance agreements are also available from the company.

He mentioned that maintaining a natural turf field, counting watering and the labor of adding fertilizer and striping in between games, can run as much as $45,000 a year.

Celenza said his company is also able to design graphics to go in the center of the field as well as designs for the end zone areas of the field. The fields are striped when they are installed but striping can also be added with water soluble paint, if desired.

Regarding health issues with the turf, “there have been a lot of studies done about the safety of recycled rubber,” he said. He said the industry was awaiting an Environmental Protection Agency report about the safety of recycled rubber at the end of 2016, but it was never released. “More than 90 separate tests have been done on recycled rubber and none have ever failed,” he said, suggesting that health claims are inaccurate. He said there are other options besides rubber, such as coconut infill. Those alternatives, however, are more expensive and have not been tested as extensively as the recycled rubber.

In this part of the country, Celenza said, there may be a need to clear snow off the fields if a team wanted to practice, say, in February or early March. He said about 20 percent of the fields he is aware of regularly plow the fields off; the rest wait for the sun to melt the snow. He said plowing has to be done carefully or else the infill will be dragged out of the fibers. He said typically, the plows leave about an inch of snow on the field, which quickly melts.

The fibers in the turf field has about a 15-yar lifespan, said Celenza. Even if the fiber, “green part,” is replaced, the leveling and ground work beneath it is usually good for a lifetime. If replacing a turf field in 15 years, the district would just place another one over the same ground with perhaps a bit of earth work needed.

Rockhill said the benefit of having an artificial turf field would be that more teams could play on it, freeing up the grass fields and allowing them to relax and recharge. It would also allow major rehabilitation work to be done on the grass fields without losing sports seasons because of the field work.

Board member Pam Carbone asked those gathered why they supported artificial turf, reminding them that a December 2008 capital project that featured an artificial turf field at S-G was roundly defeated. “That is still in the back of my mind,” she said. “This is not a luxury. How do we convince people that this is what we need?”

John Geniti, Lincoln principal and athletic director at the time, said that times have changed. He said many more children are involved in the community sports program, which provides a feeder program for the school sports. Also, the economy had just crashed in the fall of 2008 and the community was hesitant to embark on debt without knowing how the economy would be doing in the future.

Celenza said construction of a turf field takes 8 to 10 weeks, from beginning to end. He said the projects are often delayed by “politics, architects and bidding.” He noted that his company is now doing several fields through the state’s contracting system, which allows school districts to avoid bidding because the state has already bid those services and gotten the lowest price.